Also, the orbital speeds of stars in elliptical galaxies are too high to be explained by the gravitational force of just the luminous matter in the galaxies. The extra gravitational force is supplied by the dark matter in the ellipticals.

This material (including images) is copyrighted!. See my copyright notice for fair use practices. Links to external sites will be displayed in another window.

The curvature of the universe is determined by the density of the universe. You can do a cosmic inventory of all of the mass from ordinary matter in a representative region of the universe to see if the region's density is above the critical density. Such an inventory gives 10 to 20 times too little mass to close the universe. The primordial deuterium abundance provides a sensitive test of the density of ordinary matter in the early universe. Again, you get 15 to 20 times too little mass to close the universe. However, these measurements do not take into account all of the dark matter known to exist. Dark matter is all of the extra material that does not produce any light, but whose presence is detected by its significant gravitational effects.

Also, the orbital speeds of stars in elliptical galaxies are too high to be explained by the gravitational force of just the luminous matter in the galaxies. The extra gravitational force is supplied by the dark matter in the ellipticals.

Current tallies of the total mass of the universe (visible and dark matter) indicate that there is only 32% of the matter needed to halt the expansion---we live in an open universe. Ordinary matter amounts to almost 5% and dark matter makes up the other 27%. One possible dark matter candidate was the neutrino. There are a lot of them, they have neutral charge and photons do not bump into them. Unfortunately, their mass is too small and they move much too fast to create the clumpy structure we see of the dark matter and ordinary matter. The universe would not have been able to make the galaxies and galaxy clusters if the dark matter was neutrinos. To create the lumpy universe, astronomers are looking at possible massive neutral particles that move relatively slowly. Various candidates fall under the heading of "WIMPs"—weakly interacting massive particles (sometimes, astronomers & physicists can be clever in their names). Another possible dark matter candidate was simply ordinary matter locked up in dim things like white dwarfs, brown dwarfs, neutron stars, or black holes in the halos of the galaxies. These massive compact halo objects ("MACHOs") can be detected via microlensing like that used to detect exoplanets. Some MACHOs have been found but the number (and resulting total mass) of them appears to be much too small to account for the dark matter. Big Bang nucleosynthesis and the microwave background radiation (as described below) also provide a strict upper limit on the amount of ordinary matter that could produce the MACHOs in any case. As if the dark matter mystery were not enough, astronomers and physicists have now found that there is an additional form of energy not associated with ordinary or dark matter, called "dark energy", that has an even greater effect on the fate of the universe. This is discussed in the last section of this chapter.

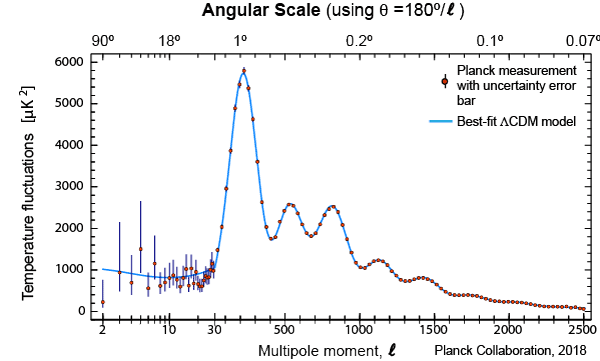

An independent way to measure the overall geometry of the universe is to look at the fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background radiation. If the universe is open (saddle-shaped), then lines starting out parallel will diverge (bend) away from each other. This will make distant objects look smaller than they would otherwise, so the ripples in the microwave background will appear largest on the half-degree scale. If the universe is flat, then lines starting out parallel will remain parallel. The ripples in the microwave background will appear largest on the 1-degree scale. If the universe is closed, the lines starting out parallel will eventually converge toward each other and meet. This focusing effect will make distant objects look larger than they would otherwise, so the ripples in the microwave background will appear largest on scales larger than 1-degree. Select the image below to go to the WMAP webpage from which the image came.

The resolution of the COBE satellite was about 7 degrees---not good enough to definitively measure the angular sizes of the fluctuations. After COBE, higher-resolution instruments were put up in high-altitude balloons and high mountains to observe the ripples in small patches of the sky. Those experiments indicated a flat geometry for the universe (to within 0.4% uncertainty). Cosmologists using the high resolution of the WMAP satellite to look at the distribution of sizes of the ripples confirmed that conclusion using its all-sky map of the microwave background at a resolution over 30 times better than COBE. WMAP also gave a much improved measurement of the ripples. The distribution of the ripples peaks at the one-degree scale---the universe is flat, a result confirmed by the even higher precision Planck satellite with over 2.5 times higher resolution than WMAP.

This result from the WMAP and Planck satellites and the too meager amount of matter in the universe to make the universe geometry flat along with the observed acceleration of the universe's expansion rate (discussed in the last section of this chapter) are forcing astronomers to conclude that there is another form of energy that makes up 68.5% of the universe (called "dark energy" for lack of anything better). The "dark energy" is probably the "cosmological constant" discussed in the last section of this chapter. Furthermore, the distribution of the sizes of the ripples shows that some sizes are preferred and other sizes are damped out as would be the case if the dark matter was different from ordinary matter. The size distribution (the spectrum of sizes) gives the ratio of dark matter to ordinary matter. Dark matter not made of atoms or other particles in the Standard Model makes up 26.5% of the critical density, leaving just 5.0% of the universe with what the rest of the previous chapters of this website have been about (ordinary matter). That ratio matches up very nicely with the ratios found using the other independent methods of Big Bang nucleosynthesis and the motions of galaxies.

In addition to the dark energy, dark matter, and ordinary matter terms, the model used to fit the observed spectrum of the sizes of the ripples and the polarization spectrum also includes terms for how far sound waves traveled when the microwave background photons were released, the scattering of the microwave background photons by high energy electrons in galaxy clusters, and a couple of terms for the density fluctuations at the end of the "inflation period" described in the last section of this chapter. The closest or best fit of the model to the ripple size and polarization spectra can be used to derive what the Hubble Constant should be for today. The result is 67.4 km/sec/Mpc with an uncertainty of just 0.5 km/sec/Mpc.

![]() Go back to previous section --

Go back to previous section --

![]() Go to next section

Go to next section

last updated: June 28, 2022