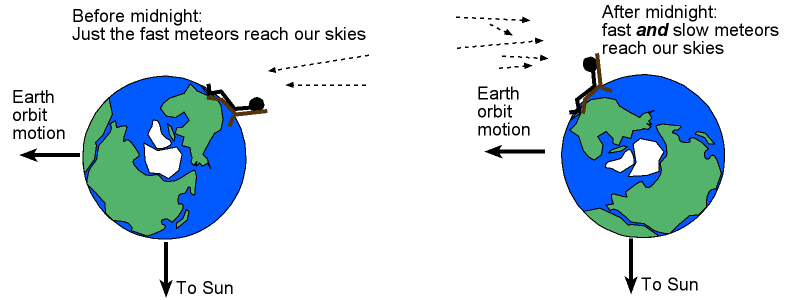

The quick flashes of light in the sky most people call ``shooting stars'' are meteors---pieces of rock glowing from friction with the atmosphere as they plunge toward the surface at speeds around 20 to 40 kilometers/second. Before the rock hits the Earth's atmosphere it called a meteoroid. Most of the meteors you see are about the size of a grain of sand and burn up at altitudes above 50 kilometers (in the mesosphere). If the chunk of rock is a meter or larger in size, it is called an asteroid. Large meteors and asteroids can make the much brighter "fireballs" that may even briefly rival the brightness of the Sun. More meteors are seen after midnight because your local part of the Earth is facing the direction of its orbital motion around the Sun. Meteoroids moving at any speed can hit the atmosphere. Before midnight your local part of the Earth is facing away from the direction of orbital motion, so only the fastest moving meteoroids can catch up to the Earth and hit the atmosphere. The same sort of effect explains why an automobile's front windshield will get plastered with insects while the rear windshield stays clean.

If the little piece of rock makes it to the surface without burning up, it is called a meteorite. As with the asteroids, there are many ways of grouping meteorites. Just as was done for the asteroids, you can group the meteorites into three basic types based on their composition.

The oldest of the stone meteorites are the carbonaceous meteorites. They contain silicates, carbon compounds (giving them their dark color), and a surprisingly large amount of water (about 22% of their mass). They are probably chips of C-type asteroids. Some of the carbonaceous meteorites have organic molecules called amino acids. Amino acids can be connected together to form proteins that are used in the biological processes of life. There is the possibility that meteorites like these may have been the seeds of life on the Earth. In addition, these type of meteorites may have provided the inner planets with a lot of water. The terrestrial planets may have been so hot when they formed that most of the water in them at formation evaporated away to space. The impact of millions to billions of carbonaceous meteorites (and comets) in the early solar system may have replenished the water supply on the terrestrial planets.

About 10% to 12% of the stones are from the crust of differentiated parent objects. Therefore, they are younger (only 4.4 billion years old). The lighter-colored stones are chips from the S-type of asteroids.

The primitive meteorites are probably the most important ones because they hold clues to the composition and temperature in various parts of the early solar nebula. Because of this, some astronomers put the meteorites into two groups: primitive and processed (not primitive).

See Arizona State University's Center for Meteorite Studies excellent website for more details about meteorites and distinguishing them from terrestrial rocks.

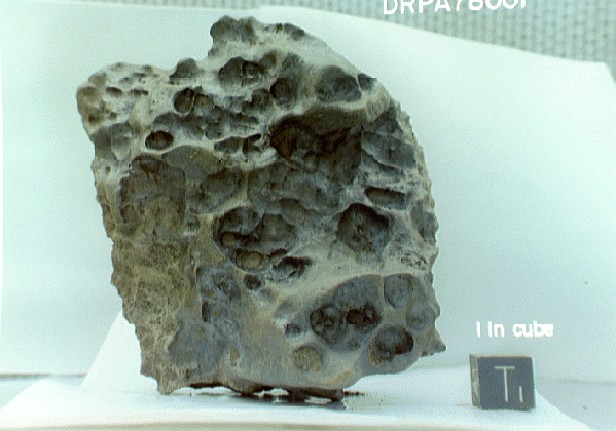

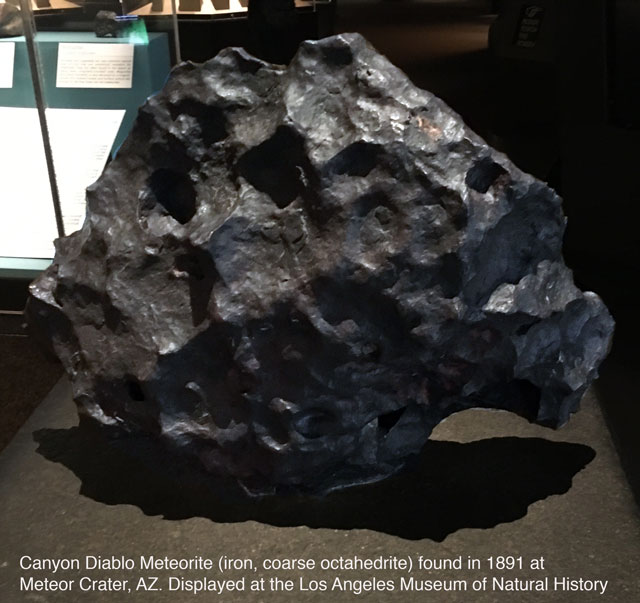

Here are some images of the meteorites on display at the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History plus a display of "meteor-wrongs"---terrestrial rocks that look like meteorites.

--

--

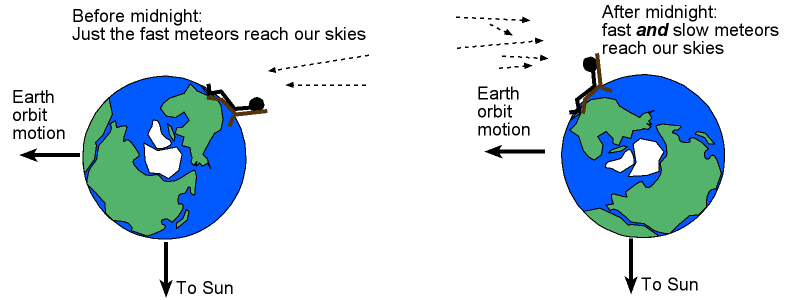

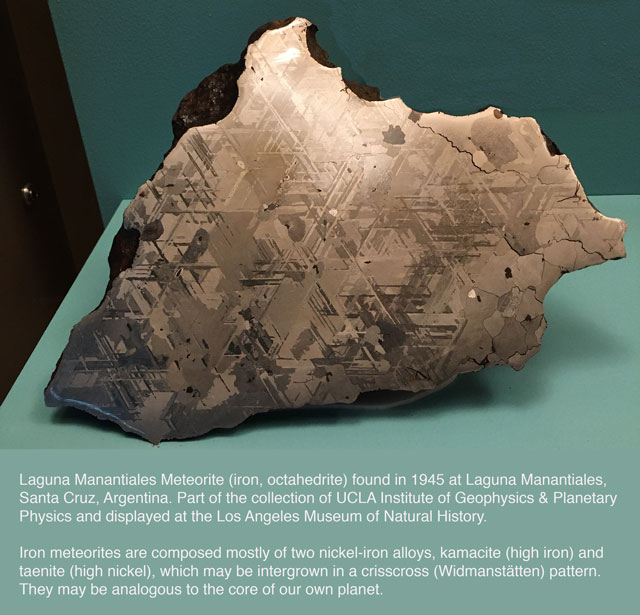

Two iron meteorites. On the left is a Canyon Diablo meteorite found at Meteor Crater in Arizona in 1891. It is a coarse octahedrite iron meteorite. On the right was found in 1945 at Laguna Manatiales, Santa Cruz in Argentina. This one clearly shows the Widmanstatten pattern of two nickel-iron alloys (kamacite with high iron and taenite with high nickel) intergrown in in a crisscross pattern. Iron meteorites are analagous to the iron cores of planets.

--

--

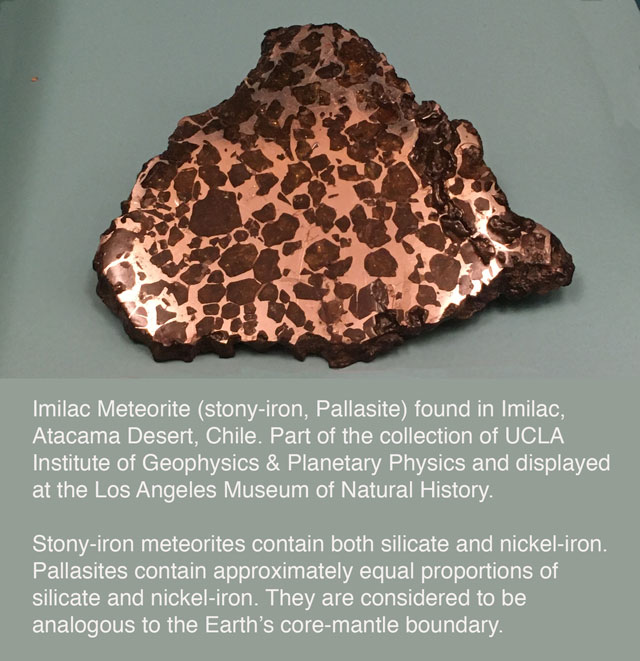

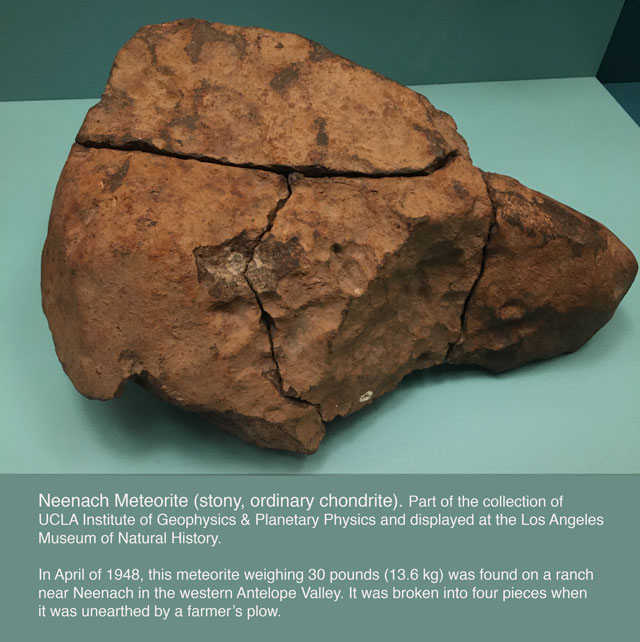

A stony-iron (on left) and a stony meteorite (on right). The stony-iron meteorite is a Pallasite found in Imilac in the Atacama Desert of Chile. Stony-iron meteorites contain both silicate and nickel-iron and Pallasites (named after the asteroid Pallas) contain approximately equal proportions of silicate and nickel-iron. Stony-irons are analogous to a planet's core-mantle boundary which is why there are so few of them found. The stony meteorite is a ordinary chondrite (has a lot of tiny spherical silicate chondrules embedded in it) found on a ranch near Neenach in the western Antelope Valley area of California. The rancher broke it into four pieces as he unearthed it with his plow.

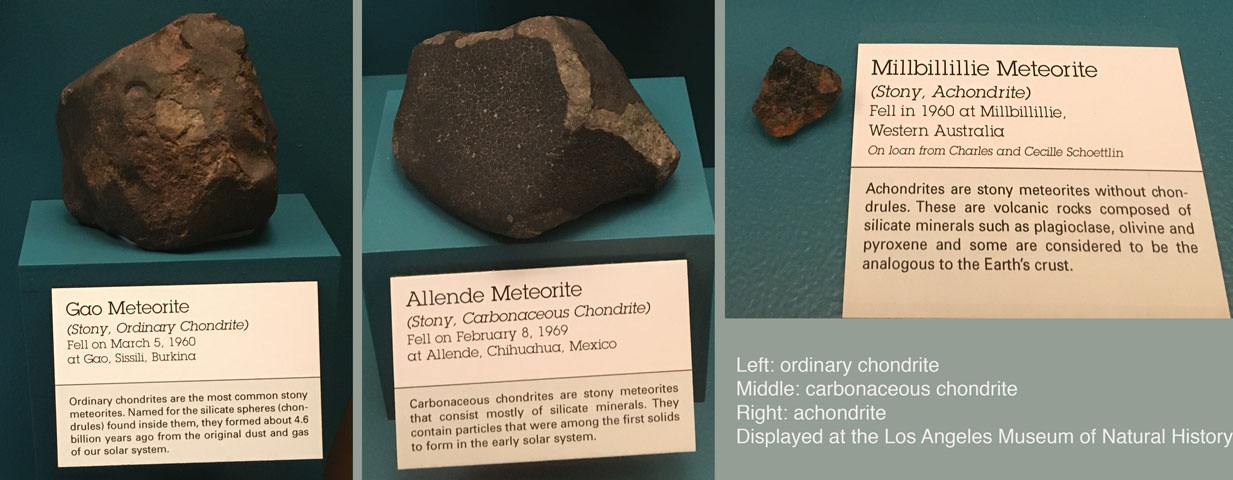

Stony meteorites: ordinary chondrite on left observed to fall on March 5, 1960 in Gao, Sissili, Burkina; carbonaceous chondrite (has a high carbon content) in the middle observed to fall on February 8, 1969 at Allenda, Chihuahua, Mexico; and an achondrite (without chondrules) that fell sometime in 1960 at Millbillillie in Western Australia. Ordinary chondrites and carbonaceous chondrites are the oldest of the meteorites that formed 4.6 billion years ago in the birth of the solar system. The achondrite meteorite is made of igneous rocks composed of silicate minerals such as plagioclase, olivine, and pyroxene and is analogous to a planet's crust.

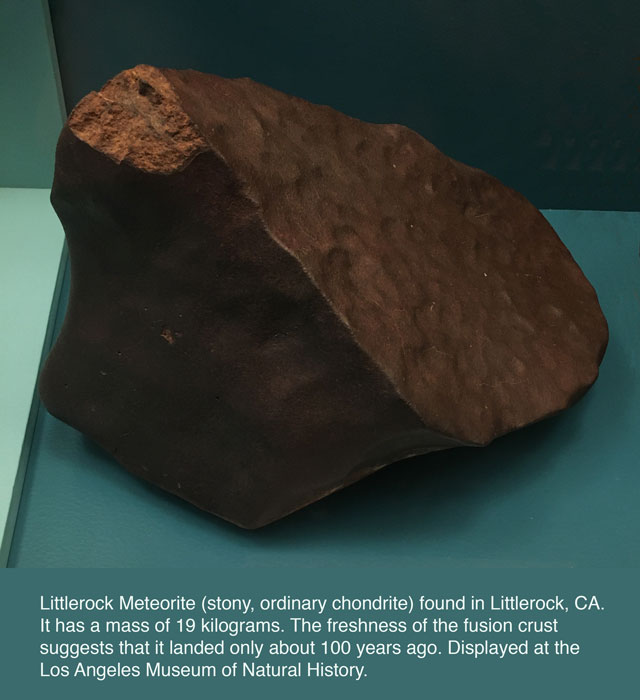

Named for where it was found in Littlerock, California, this stony ordinary chondrite has a mass of 19 kilograms. It probably fell about 100 years ago, judging by the freshness of the fusion crust---the outer crusty layer that forms as the rock heats up when passing through the atmosphere at supersonic speeds.

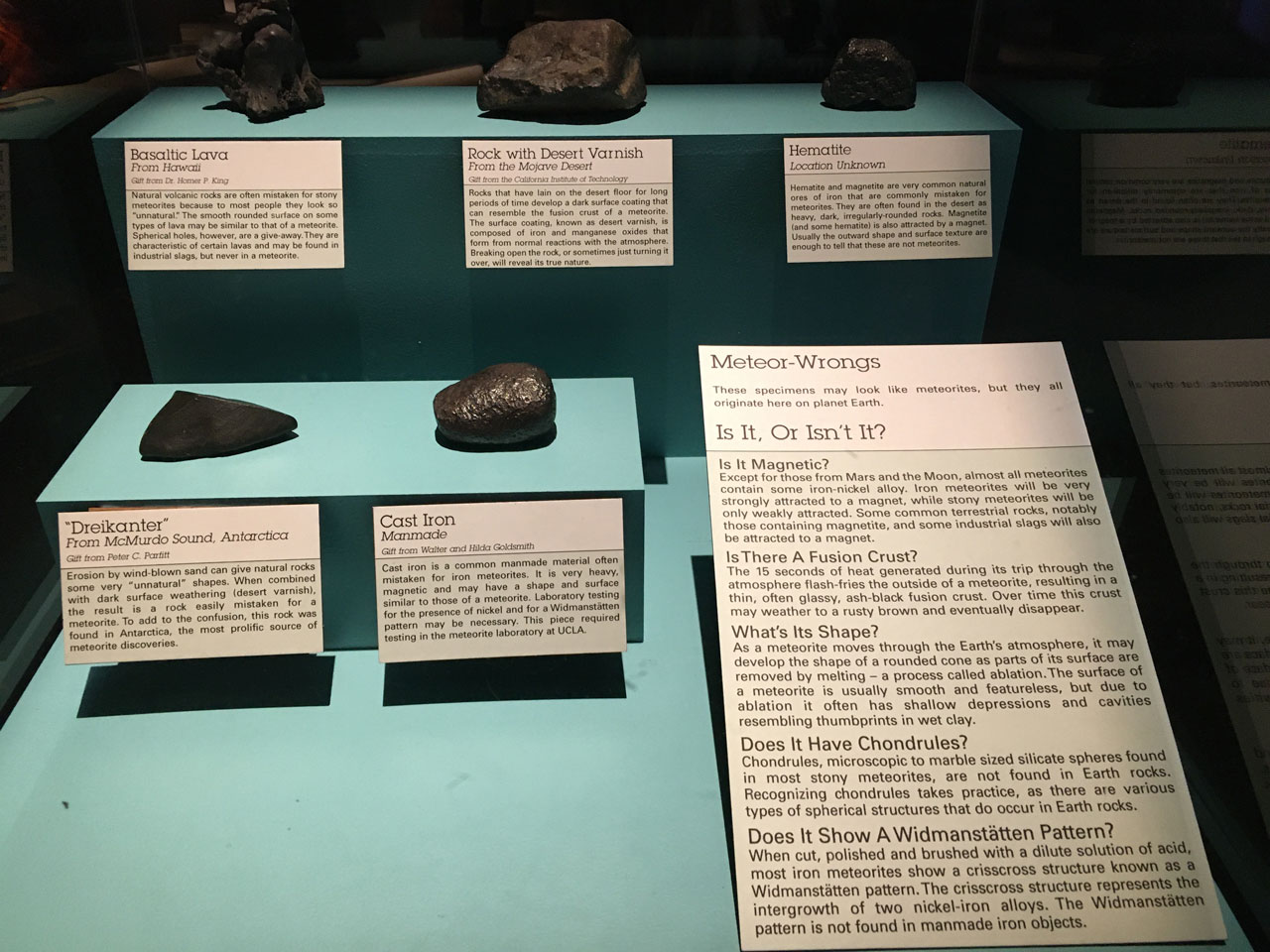

Finally, a set of "meteor-wrongs"---Earth rocks that look like extra-terrestrial meteorites. Here are the questions to ask when looking at a rock to determine if it might be a meteorite:

I sometimes get asked to identify a strange looking rock that's posing as a meteorite. I send inquirers to the William M Thomas Planetarium's "Is it a Meteorite or a Meteorwrong?" page. A definite positive identification requires chemical analysis at a meteorite laboratory.

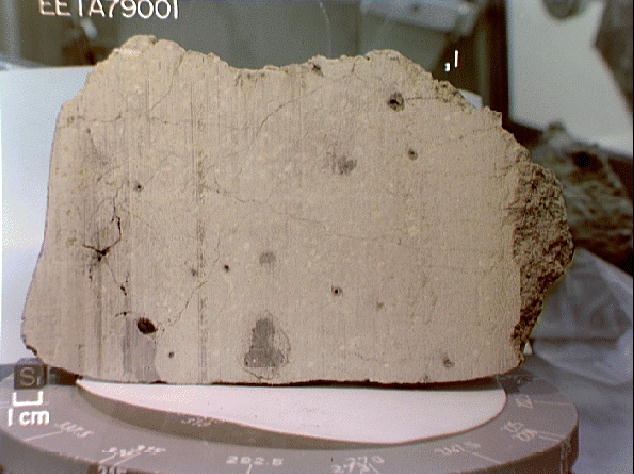

To get an accurate number for the proportion of meteorites that fall to the Earth (an unbiased sample), meteorite searchers go to a place where all types of rocks will stand out. The best place to go is Antarctica where the stable, white ice pack makes darker meteorites easy to find. Meteorites that fell thousands of years ago can still be found in Antarctica without significant weathering. Since the 1980s, thousands of meteorites have come from here. For further exploration, check out the Antarctica Meteorite web site at the Planetary Materials Curation office of NASA and the ANSMET site at Case Western Reserve University.

Most (about 99.8%) meteorites are pieces of asteroids, but 143 (at the time of writing) are from the Moon. A select few (125 at the time of writing), the Shergotty-Nakhla-Chassigny (SNC) meteorites, may be from Mars. The relative abundances of magnesium and heavy nitrogen (N-15) gases trapped inside the SNC meteorites is similar to the martian atmosphere as measured by the Viking landers and unlike any meteorites from the asteroids or Moon. Also, the isotope ratios of argon and xenon gas trapped in the meteorites most closely resemble the martian atmosphere and are different than the typical meteorite. The analysis of the soil and rocks by the Mars Pathfinder confirm this.

Most SNC meteorites are younger than 1.4 Gyr old, but the one with suggestions of extinct Martian life is about 4.5 Gyr old. The discovery was published in the August 16, 1996 issue of the journal Science. Non-subscribers can find a copy of the article here. Recent studies of the meteorite have cast considerable doubt on the initial claims for fossil microbes in the rock. There is strong evidence of contamination by organic molecules from Earth, so this meteorite does not provide the conclusive proof hoped for. A detailed description of SNC meteorites is given at JPL's Mars Meteorites website.

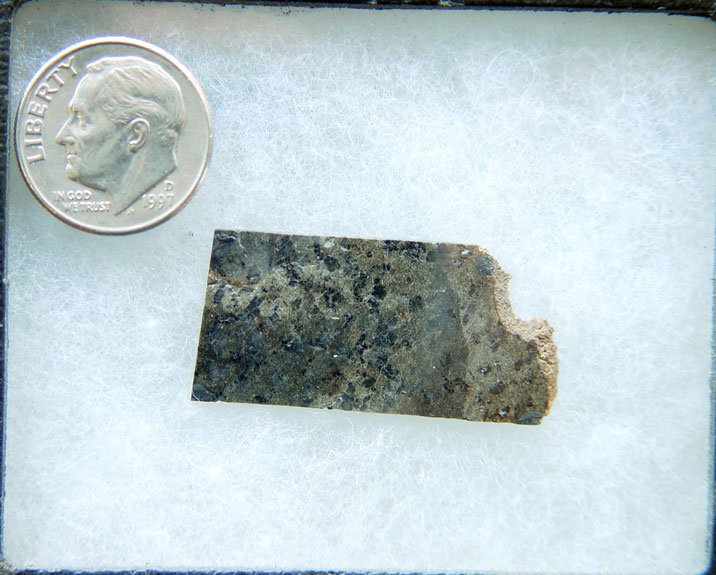

Below are some small slices of martian meteorites I got to handle at a Chautauqua short course in 2005, courtesy of Tony Irving. One of them, the Zagami meteorite slice, had been analyzed enough (and handled by several intermediary parties at least) that we were allowed to touch it directly, so I can say that I have touched a piece of Mars! Note that the martian rocks are not red but instead, grayish in color like the rocks of Earth. The red color of Mars is from a thin layer of dust on the surface. When the dust is swept away by a dust devil or a rover from Earth, the darker material below is exposed. In all of the images, a U.S. dime coin is used to show the scale of the image.

![]() Go back to previous section --

Go back to previous section --

![]() Go to next section

Go to next section

last updated: June 8, 2022