There are millions of boulder-size and larger rocks that orbit the Sun, most of them between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Some asteroids called Trojan asteroids travel in or near Jupiter's orbit about 60 degrees ahead of Jupiter and 60 degrees behind Jupiter (gravity balance points between Jupiter and the Sun). Some asteroids have orbits that bring them close to Earth's orbit, some even crossing the Earth's orbit. These are called Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs) and include some 2366 (as of September 2023) "Potentially Hazardous Asteroids" with the greatest potential of very close approaches to Earth. Comets that get near the Earth and NEAs are lumped together in Near-Earth Objects (NEOs). A plot of the known asteroids is available at the Minor Planet Center.

About one million of them are larger than 1 kilometer across. Those smaller than about 300 kilometers across have irregular shapes because their internal gravity is not strong enough to compress the rock into a spherical shape. The largest asteroid is Ceres with a diameter of 1000 kilometers. Pallas and Vesta have diameters of about 500 kilometers and about 15 others have diameters larger than 250 kilometers. The number of asteroids shoots up with decreasing size. The combined mass of all of the asteroids is about 25 times less than the Moon's mass (with Ceres making up over a third of the total). Very likely the asteroids are pieces that would have formed a planet if Jupiter's strong gravity had not stirred up the material between Mars and Jupiter. The rocky chunks collided at speeds too high to stick together and grow into a planet.

Though there are over a million asteroids, the volume of space they inhabit is very large, so they are far apart from one another. Unlike the movie The Empire Strikes Back and other space movies, where the spacecrafts flying through an asteroid belt could not avoid crashing into them, real asteroids are at least tens of thousands of kilometers apart from each other. Spacecraft sent to the outer planets have travelled through the asteroid belt with no problems (and no swerving about).

There are several possible ways of grouping asteroids. Astronomers use schemes of varying complexities based on composition, orbit characteristics or some combination of both. The simplest way puts them into three basic types based on their composition:

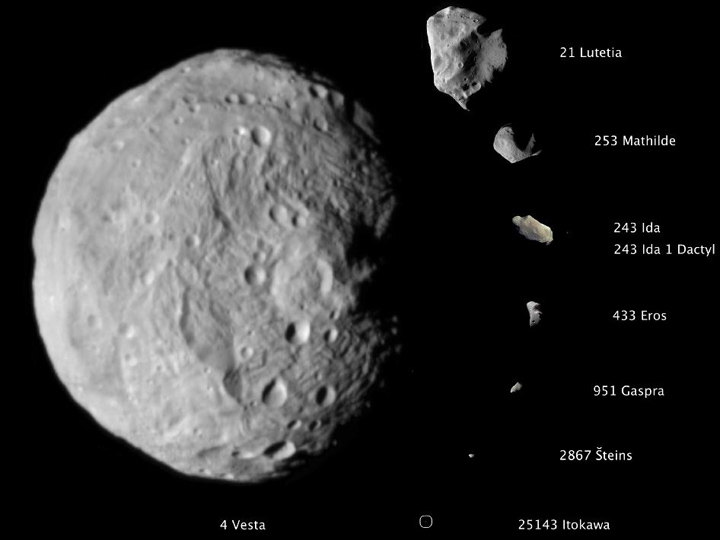

Note their irregular shapes! Small bodies can have irregular shapes because their gravity is too weak to crush the material into the most compact shape possible: a sphere. Depending on the strength of the material of which they are made, the largest non-spherical asteroids (and moons) can have diameters of roughly 360 to 600 kilometers. Planets are much too large (have too much gravity) to be anything but round. Ceres, the largest asteroid, is large enough to be round and is now re-classified as a "dwarf planet" (along with Pluto, Charon, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake).

The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched a spacecraft called Hayabusa to land and extract a sample from Itokawa, a small near-Earth S-type asteroid only half a kilometer in length (535 x 294 x 209 meters). Hayabusa collected at least one sample from the asteroid's surface and returned to Earth in June 2010. Below are images of Itokawa from Hayabusa when it was just 7 kilometers from the asteroid. It has a rough surface but very few impact craters. Itokawa is basically a rubble pile formed by the ejecta from a large impact on a larger object coming back together gravitationally. Its composition is very much like the chondrite meteorites with little iron or other metals.

Itokawa + 270 deg surface |

Itokawa + 90 deg surface |

JAXA followed up with Hayabusa2 that was sent to Ryugu, a near-Earth C-type asteroid about 865 meters across. Hayabusa2 reached Ryugu in late July 2018 and deployed several small landers in October 2018. Hayabusa2 collected three samples from Ryugu in 2019 and returned them to Earth in early December 2020, including one sample from inside a crater created by shooting a copper projectile into Ryugu, so we could get a sample from Ryugu's interior.

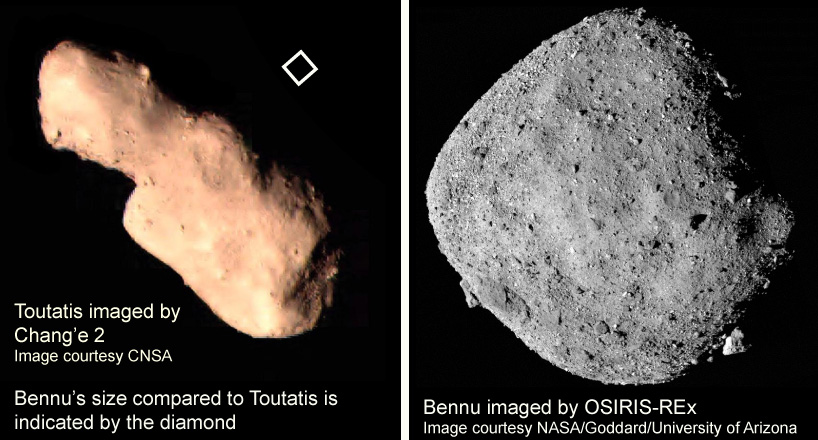

Above are the near-Earth asteroids Toutatis imaged by the Chinese lunar probe Chang'e 2 and Bennu imaged by OSIRIS-REx. Toutatis was imaged from a distance of just 93 kilometers away, though the spacecraft got to within 3.2 kilometers at closest approach. Toutatis was about 6.9 million kilometers from the Earth when it passed by us in December 2012. Toutatis is 4.5 x 2.4 x 1.9 kilometers in size and like Itokawa, it is probably a rubble pile from the merging of two bodies. The size comparison of Bennu (just 524 meters in diameter) to Toutatis is indicated by the diamond to the upper right of Toutatis. Toutatis passes close to the Earth approximately every four years. The next time it will pass even closer will be in November 2069 but at a still safe distance of 3 million kilometers (7.7 lunar distances).

The Bennu image is from a distance of 24 kilometers. Two large boulders on the southern limb of Bennu are clearly visible. Like Itokawa, Bennu is a rubble pile that formed from one or more breakups in its history but its shape is like Ryugu's (though half the size of Ryugu). Bennu is rich in carbon, organic molecules, and hydrated minerals. Bennu comes very close to Earth every six years and there is a 0.037% of hitting Earth between 2175 and 2199 (see also OSIRIS-REx's report about Bennu's future orbit). From an orbit less than two kilometers from Bennu's center, OSIRIS-REx did very high-resolution mapping and spectroscopy of Bennu’s surface and its gravity field to determine Bennu’s interior structure as well as finding the best spot to extract a sample to return to Earth. This intense scrutiny of Bennu before collecting a sample took over a year and half because Bennu turned out to be a lot rockier than expected, covered in boulders. In October 2020 OSIRIS-REx collected about 250 grams of Bennu material. Further study of Bennu followed until May 2021 when OSIRIS-REx headed back to Earth. OSIRIS-REx arrived back at Earth in September 2023 to return the sample in the Sample Return Capsule which landed in the Utah Testing and Training Range about 85 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah.

The sample from Bennu contain life's key building blocks. The Bennu sample has a lot of carbon, nitrogen, and ammonia. The team found 33 amino acids, including 14 of the 20 that make up the proteins of life on Earth, and all five nucleobases that make up DNA and RNA. While amino acids and other organic molecules have been found in meteorites before, there is the possibility that the rocks were contaminated as they fell to the ground after reaching the ground. The Bennu material is absolutely pristine, with no contamination possible. Assuming that other carbon-rich asteroids are like Bennu, the building blocks of life could have been delivered all over the solar system. In addition, the sample indicates that the parent body from which Bennu broke off had saltwater on it. A briny broth could have allowed the building blocks of life to combine and intermingle. The ingredients and environments for life are indeed found beyond Earth. Did the transition from chemistry to biology happen in those suitable environments is the big question that we can only answer by bringing back samples from the planets and moons (particularly, Mars, Europa, Titan, and Enceladus).

In late September 2007, NASA launched the Dawn spacecraft to explore the two largest asteroids, Ceres (about 960 km in diameter) and Vesta (530 km in diameter), originally for about six months at each asteroid (Dawn's time at Vesta was extended to a full year). Vesta was explored from August 2011 to August 2012. Dawn the traveled across the asteroid belt for 2.5 years and arrived at Ceres in February 2015. Dawn explored Ceres until November 2018 when it ran out of propellant to keep its radio antenna pointed at Earth. Dawn remains in orbit around Ceres. Below left are the best pictures we have of these asteroids (both the Vesta image and the Ceres image are from the Dawn spacecraft) and how they compare to the much smaller Eros asteroid that was explored by the NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft. Below right is a comparison of the two asteroids with the two smallest planets in our solar system. The Dawn spacecraft's primary goal was to help us figure out the role of size and water in determining the evolution of the planets. Ceres is a primitive and relatively wet protoplanet (with possibly almost five times the amount of fresh water on the Earth) while Vesta has changed since it formed and is now very dry. At nearly the same distance from the Sun, why did these two bodies become very different?

|

|

Some initial findings from Dawn about Vesta include: Vesta once had a subsurface magma ocean—when Vesta was almost completely melted. It has a differentiated interior or a crust, mantle, and core. Dawn confirmed that three classes of meteorites used by meteorite scientists (howardite, eucrite and diogenite meteorites) do in fact come from Vesta. Those types of meteorites account for about 6 percent of all meteorites falling on Earth, making Vesta one of the largest single sources for Earth's meteorites. Vesta does have some minerals that are chemically bound with water ("hydrated minerals") and much of the water was originally delivered as part of Vesta's formation over a small time-frame, rather than primarily as a result of comet collisions later in its history as what produced the water ice found in sheltered craters at the poles of the Moon and Mercury always shut off from sunlight. Vesta also has some very dark patches from impacts with carbon-rich asteroids.

Vesta's topography is steeper and more varied than originally expected. Some of the crater walls are almost vertical instead of sloped like those on the Earth, Moon, and other worlds. It has a huge central peak in one of its impact basins that is much higher and wider, relative to crater size, than the central peaks of craters found on other bodies in the solar system. Two of the largest impact basins on Vesta are much younger than the impact basins found on the Moon. That's geologically speaking, of course. The youngest impact basin on Vesta is about a billion years old while the Moon's impact basins, including the ones making the dark, smooth maria are about 3.8 billion years old. Some of the craters have short, wide, straight gullies in the crater walls formed from flows of sand-like material and some gullies that are much longer, narrower, and curvier than would be formed from sand-like material flowing downward. Such sinuous gullies on the Earth are carved by liquid water and those on Mars are from water, carbon dioxide, or other mechanism. Clearly, the geology of Vesta is more complex than originally thought!

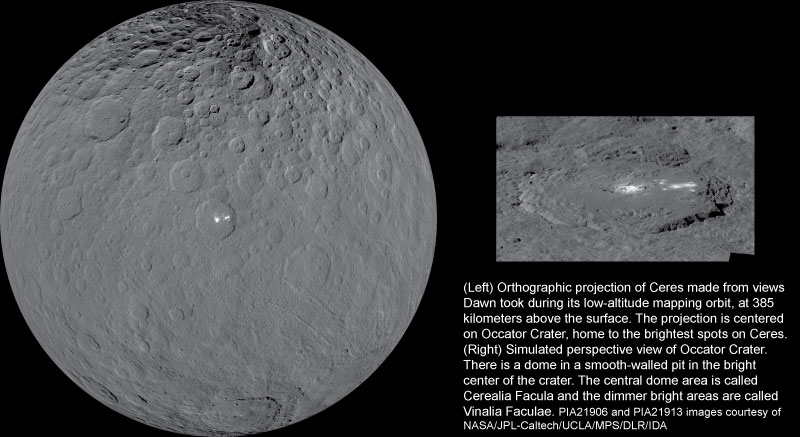

Ceres was originally an ocean world where ammonia and water reacted with silicate rocks (about 25% of its mass is ice). When Ceres cooled and froze, the carbonates and other salts concentrated into deposits that are now exposed in locations across the surface, including the very bright spots in Occator Crater (see the figure below). Ceres also has organic molecules on its surface. Ceres has a strong crust made of hydrated salts, rocks, and clathrates on top of a differentiated interior. Ceres also appears to have recent, maybe ongoing, geologic activity despite its small size. Perhaps the salts enable some of the interior water to remain liquid. The presence of ammonia on Ceres suggests that Ceres might have originally come from the outer solar system and then got its orbit changed from the reshuffling events that happened in the early solar system (see the Solar System Formation page for more about that). More discoveries will happen as scientists pore over all of the data beamed back to Earth by Dawn.

On the left is an orthographic projection of Ceres put together from images Dawn took during its low-altitude mapping orbit, at 385 kilometers above the surface. The projection is centered on Occator Crater, home to the brightest spots on Ceres. Occator is centered at 20 degrees north latitude, 239 degrees east longitude. On the right is a simulated perspective view of Occator Crater. Dawn's close-up view reveals a dome in a smooth-walled pit in the bright center of the crater. Numerous linear features and fractures crisscross the top and flanks of this dome. Prominent fractures also surround the dome and run through smaller, bright regions found within the crater. The central dome area is called Cerealia Facula and the dimmer bright areas are called Vinalia Faculae.

A few other asteroids have surfaces made of basalt from volcanic lava flows. When asteroids collide with one another, they can chip off pieces from each other. Some of those pieces, called meteoroids if they are less than a meter in size, can get close to the Earth and be pulled toward the Earth by its gravity.

![]() Go back to previous section --

Go back to previous section --

![]() Go to next section

Go to next section

last updated: April 7, 2025