Observation: During a solar eclipse you see that the stars along the same line of sight as the Sun are shifted ``outward''. This is because the light from the star behind the Sun is bent toward the Sun and toward the Earth. The light comes from a direction that is different from where the star really is. But wouldn't Newton's law of gravity and the result from Einstein's Special Relativity theory that E = mc2 predict light deflection too? Yes, but only half as much. General Relativity says that time is also stretched so the deflection is twice as great.

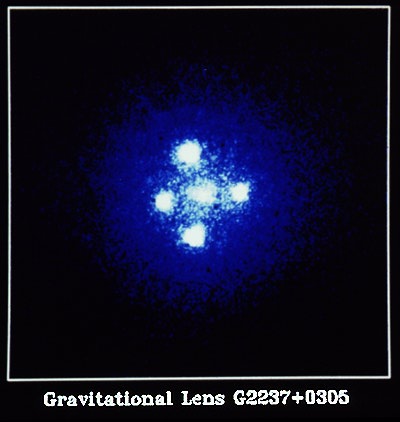

Observation: The light from quasars is observed to be bent by gravitational lenses produced by galaxies between the Earth and the quasars. It is possible to see two or more identical images of the same background quasar. In some cases the light from background quasars or galaxies can be warped to form rings. Since the amount of warping depends on the mass of the foreground galaxy, you can estimate the total mass of the foreground galaxy.

The Einstein Cross (Q2237+0305) is formed by a foreground galaxy lensing the light from a background quasar into 4 images.

|

Image courtesy of Bill Keel. Galaxy nucleus produces the image. Zoomed-in image of nucleus on right. |

Image courtesy of the Space Telescope Science Institute |

Below is a picture from the Hubble Space Telescope showing the lensing of a background galaxy by a cluster of galaxies in front. The distorted blue arcs visible around the center of the picture are the lensed background galaxy. If you select the image, an enlarged version will appear (courtesy of the Space Telescope Science Institute). The observations of gravitational lensing are now so commonplace, that we use it to map out the distribution of dark matter (see also this link), to examine extremely distant objects that have been magnified enough for us to study and would have otherwise been undetectable, and to look for exoplanets.

Observation: a) Clocks on planes high above the ground run faster than those on the ground. The effect is small since the Earth's mass is small, so atomic clocks must be used to detect the difference. b) The Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) system must compensate for General Relativity effects or the positions it gives for locations would be significantly off.

This is a consequence of time dilation. Suppose person A on the massive object decides to send light of a specific frequency f to person B all of the time. So every second, f wave crests leave person A. The same wave crests are received by person B in an interval of time interval of (1+z) seconds. He receives the waves at a frequency of f/(1+z). Remember that the speed of light c = (the frequency f) × (the wavelength l). If the frequency is reduced by (1+z) times, the wavelength must INcrease by (1+z) times: lat B = (1+z) × lat A. In the doppler effect, this lengthening of the wavelength is called a redshift. For gravity, the effect is called a gravitational redshift.

Observation: spectral lines from the top layer of white dwarfs are significantly shifted by an amount predicted for compact solar-mass objects. The white dwarf must be in a binary system with a main sequence companion so that the amount the total shift due to the ordinary doppler effect can be determined and subtracted out. Inside a black hole's event horizon, light is redshifted to an infinitely long wavelength.

Observation: Before September 14, 2015, the most sensitive detectors had not directly detected the tiny stretching-shrinking of spacetime caused by a massive object moving. On that date the twin LIGO detectors (described below) detected the "chirp" of two merging stellar-mass black holes. Until then, the best evidence we had for gravitational waves came from the observations of the decaying orbits of a binary pulsar system discovered in 1974 by Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor. The spiraling inward of the binary pulsar system can only be explained by gravity waves carrying away energy from the pulsars as they orbit each other. This observation provides a very strong gravity field test of General Relativity.

The two pulsars in the binary system called PSR1913+16 orbit each other very rapidly with a period of only 7.75 hours in very eccentric and small elliptical orbits that bring them as close as 766,000 kilometers and then move them rapidly to over 3.3 million kilometers apart. Because of their large masses (each greater than the Sun's mass) and rapidly changing small distances, the gravity ripples should be noticeable. Hulse and Taylor discovered that the orbit speed and separation of PSR1913+16 changes exactly in the way predicted by General Relativity. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for this discovery.

However, this is an indirect observation of gravitational waves. The first direct detection of gravitational waves occurred in mid-September 2015 (but announced February 11, 2016) with twin LIGO detectors in Hanford, WA and Livingston, LA (both USA) when ripples of spacetime from the last fraction of a second of the merger of two black holes with masses 29 and 36 solar masses combined to form a 62-solar mass black hole with 3 solar masses of energy radiated away as gravitational waves in that last fraction of a second. That is about 50 times more energy produced by the rest of the visible universe!

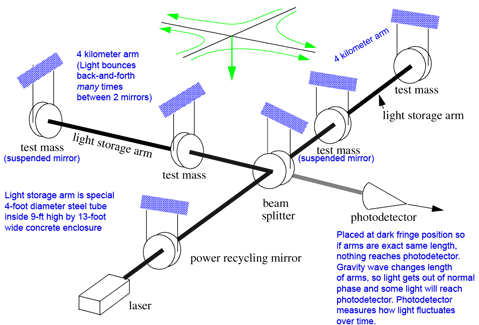

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) is an international effort to directly detect the very small ripples in spacetime passing through the Earth. The basic LIGO set up involves two several-kilometer long arms perpendicular to each other. At either end of the arms are mirrors that bounce laser light back and forth many times and then are recombined to make an interference pattern of light and dark fringes as different parts of a wave's heights and troughs cancel out or combine with another wave's heights and troughs to varying degrees. Without any spacetime ripples, the laser light waves from the two arms will perfectly cancel each other out, so nothing will reach a photodetector. A gravity wave passing through a LIGO site, will stretch one of the arms while squeezing the other arm and then reverse the effect as the gravity waves passes by. This will make the combined light from the two arms get out of phase with each other, resulting in some of the laser light reaching the photodetector. The photodetector then measures how the light fluctuates over time. The technological challenge is to detect minute changes in the length of the arms as small as 10-18 meters (many times smaller than a proton!) in the midst of all of the terrestrial "noise" such as seismic events, sloshing ocean waves hitting land, sound waves, random laser fluctuations, and thermal effects of the materials used that can easily overwhelm the very weak gravity wave ripples of spacetime. A schematic for the United States version is shown below (adapted from a diagram in a slideset from Rainer Weiss).

LIGO sites are located in the United States (at Hanford, WA and Livingston, LA), in Germany (near Hannover), in Italy (near Pisa), in Japan (at the Kamioka mine), and a future site in Australia. Early versions of LIGO did not detect any gravitational waves. These negative results were not surprising, however, as the technology innovations needed in hardware and software were still being developed along with our ability to analyze the weak waves amidst all of the noise. Between late 2010 and early 2015, Advanced LIGO was installed at the two United States sites and began observations in September 2015. Advanced LIGO increases the sensitivity of gravity wave detection by a factor of ten times. Being able to detect gravity waves from sources ten times farther away means an increase of a thousand times the volume of space or a thousand times the number of possible sources. This increased sensitivity made it possible to detect the gravitational waves from the merging black holes near the end of the first observing run in September 2015.

A lot of information about the system is encoded in the gravitational waveform. For example with merging binary systems: the amplitude of the gravitational wave depends on the masses of the merging objects and the distance of the source from us; the frequency depends on the mass and orbital period of the objects; how the frequency changes depends on the ratio of the masses; and the maximum frequency before the objects merge tells us the diameter of the objects. Because many of the parameters of the system (e.g., mass, separation distance, distance to the system, etc.) are intertwined in how they shape the gravitational waveform, scientists compare the observed waveform against a database of computed waveforms with different combinations of parameters to find the best fit as well as to sift out the gravitational wave signal from all the other terrestrial sources of noise. With the differences in time the gravitational waves hit different detectors, we can determine the direction from where the waves came.

The gravitational waves were detected by the Livingston detector 7 milliseconds before the Hanford detector as the gravitational waves traveled at the speed of light from the direction of the southern hemisphere sky, roughly in the same direction as the Large Magellanic Cloud. The source was much further away than the LMC as the gravitational waves had traveled between 700 million years to 1.6 billion years. (The detection by just two detectors makes a more precise direction and distance measurement impossible.) LIGO was able to see all three phases of the collision---inward spiral, merger, and ringing as the merged object settled down---happen in the just the way predicted by General Relativity. The increasing amplitude and frequency of the waves during the merger if converted to audio sound waves would make a sound like a chirp of a bird, so the LIGO scientists refer to it as the chirp of a black hole merger. Several other detections were made in the fall 2015 observing run and many more are expected in future observing runs as the sensitivity of Advanced LIGO is increased even further. Hopefully, with that catalog of detections, we will begin to see discrepancies from the predictions of Theory of General Relativity that will lead us to an even deeper understanding of gravity, particularly at the quantum realm.

The fifth gravitational wave event (GW170817), detected in mid-August 2017, was probably even more important than the first detection because it was the first one whose source also produced electromagnetic radiation we could observe with ground and space-based telescopes. Unlike the first four gravitational wave events that involved mergers of black holes, the fifth event involved the merger of neutron stars. The neutron stars collided into each other to create a type of explosion called a "kilonova" that is a thousand times more energetic than a normal nova. The use of the telescopes enabled us to pinpoint its location to within an elliptical galaxy called NGC 4993, 130 million light years away. Besides confirming theories about the source of some short-duration gamma-ray bursts and the formation mechanism of many of the heavy elements including platinum, lead, gold, and rare earth elements, the gravitational waves enabled us to get a distance to the galaxy independent of the usual step-by-step procedure called the "distance scale ladder". Coupling that direct distance measurement with the redshift measurements of NGC 4993 enabled astronomers to determine the Hubble Constant which is the expansion rate of the universe. Quite a lot of information from just one event! The LIGO detectors are analogous to microphones that enable us to "hear" the universe. Before we were able to detect gravitational waves, it was like we were watching silent movies about the universe (and not close-captioned either). Putting gravitational wave data together with electromagnetic radiation data gives us a richer, multi-sensory viewing of the universe.

Another laser interferometry system will be the evolving Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (eLISA) scheduled to launch in the mid-2030s. Using three satellites in an equilateral triangle formation with each side a million kilometers long, eLISA will be sensitive to a frequency range about 10 thousand times smaller than what LIGO can observe (10-4 to 10-1 for eLISA vs. 10 to 103 for LIGO). eLISA will be able to detect the gravitational waves from smaller supermassive black holes (those in the tens of thousands to few million solar mass range) and from compact binary stars. LIGO can detect gravitational waves from neutron star mergers and supernovae. See the GWPlotter by Moore, Cole, and Berry from the Gravitational Wave Group for the sensitivities of the various gravitational wave detectors and the types of objects or events they are (will be) able to detect.