This material (including images) is copyrighted!. See my copyright notice for fair use practices. Select the photographs to display the original source in another window. Links to external sites will be displayed in another window.

All galaxies began forming at about the same time approximately 13 billion years ago. The origin of galaxies and how they changed over billions of years is an active field of research in astronomy today. Models for galaxy formation have been of two basic types: "top-down" and "bottom-up". The "top-down" model on the origin of the galaxies says that they formed from huge gas clouds larger than the resulting galaxy. The clouds began collapsing because their internal gravity was strong enough to overcome the pressure in the cloud. If the gas cloud was slowly rotating, then the collapsing gas cloud formed most of its stars before the cloud could flatten into a disk. The result was an elliptical galaxy. If the gas cloud was rotating faster, then the collapsing gas cloud formed a disk before most of the stars were made. The result was a spiral galaxy. The rate of star formation may be the determining factor in what type of galaxy will form. But, perhaps the situation is reversed: the type of galaxy determines the rate of star formation. Which is the "cause" and which is the "effect"?

A variation of the "top-down" model says that there were extremely large gas clouds that fragmented into smaller clouds. Each of the smaller clouds then formed a galaxy. This explains why galaxies are grouped in clusters and even clusters of galaxy clusters (superclusters). However, the model predicts a very long time for the collapse of the super-large clouds and fragmentation into individual galaxy clouds. There should still be galaxies forming today. Astronomers looking for these nearby young galaxies focus their attention on the galaxies with very small amounts of "metals" (elements heavier than helium), particularly those with low percentages of oxygen. Recall from the stellar nucleosynthesis section that the metals are made from the stars and oxygen is the third most abundant element in the universe. Younger galaxies with younger generations of stars will have less pollution of metals in them.

The first nearby oxygen-poor galaxy discovered is "I Zwicky 18", just 60 million light years away. It has just 2.6% the amount of oxygen as the Milky Way and appears to have begun forming stars only 500 million years ago. However, further observations have revealed it does have much older stars as well and we're seeing it undergo a burst of star formation now. Its oxygen-poor composition may be due to unpolluted gas falling into the galaxy.

Another even nearer oxygen-poor galaxy, Leo P, is just 5 million light years away and has a very low star formation rate, just 1/50,000 the rate of the Milky Way. Like I Zwicky 18, Leo P also contains very old stars as well. Due to its small mass, Leo P wasn't able to hold on to its metals as supernovae blasted the metals away. It still has gas in it to make stars because it hasn't passed close to a large galaxy and had the gas stolen yet. The current record-holder for lack of oxygen is J0811+4730 with just 1.7% the amount of oxygen as the Milky Way. It is 620 million light years away and it is undergoing a burst of star formation now. Rather than being truly young galaxies, these and other oxygen-poor galaxies have kept low levels of metals because of their environment and small mass. Astronomers are now using these oxygen-poor galaxies to better understand how the universe's first galaxies formed stars billions of years ago. Observations and computer simulations show that the "bottom-up" model is how galaxies developed.

The "bottom-up" model builds galaxies from the merging of smaller clumps about the size of a million solar masses (the sizes of the globular clusters). These clumps would have been able to start collapsing when the universe was still very young. Then galaxies would be drawn into clusters and clusters into superclusters by their mutual gravity. This model predicts that there should be many more small galaxies than large galaxies---that is observed to be true. The dwarf irregular galaxies may be from cloud fragments that did not get incorporated into larger galaxies. Also, the galaxy clusters and superclusters should still be in the process of forming---observations suggest this to be true, as well.

The radio galaxy MRC 1138-262, also called the "Spiderweb Galaxy" is a large galaxy in the making. At 10.6 billion light years away, we see it in the process of forming only 3 billion years after the Big Bang. Note the small, thin "tadpole" and "chain" galaxies that are merging together to create a giant galaxy.

Astronomers are now exploring formation models with supercomputer simulations that incorporate the dark matter which makes up most of the matter in the universe. Huge dark matter clumps the size of superclusters gather together under the action of gravity into a network of filaments to make the "cosmic web" described in the previous section. Where the dark matter filaments intersect, regular matter concentrates into galaxies and galaxy clusters. The densest places with many intersecting filaments would have had more rapid star formation to make the elliptical galaxies while the lower density concentrations along more isolated filaments would have made the spiral galaxies and dwarf galaxies. In such a model, the visible galaxies ablaze in starlight are like the tip of an iceberg---the visible matter is at the very densest part of much larger dark matter chunks. Some dark matter clumps may have cold hydrogen and helium gas making "dark galaxies" that have not become concentrated enough to start star formation (see also the news site of the Dragonfly Telescope Array).

A dark matter map was published at the beginning of 2007 that probed the dark matter distribution over a large expanse of sky and depth (distance---see the "Distribution of Dark Matter" figure below). The map is large enough and has high enough resolution to show the dark matter becoming more concentrated with time. The map stretches halfway back to the beginning of the universe. It also shows the visible matter clumping at the densest areas of the dark matter filaments (see the "Distribution of Visible and Dark Matter" figure below). The dark matter distribution was measured by the weak gravitational lensing of the light from visible galaxies by the dark matter (see the relativity chapter).

Collisions take place over very long timescales compared to the length of our lifetime---several tens of millions of years. In order to study the collisions, astronomers use powerful computers to simulate the gravitational interactions between galaxies. The computer can run through a simulation in several hours to a few days depending on the computer hardware and the number of interacting points. The results are checked with observations of galaxies in different stages of interaction. Note that this is the same process used to study the evolution of stars. The physics of stellar interiors are input into the computer model and the entire star's life cycle is simulated in a short time. Then the results are checked with observations of stars in different stages of their life.

In the past, computer simulations used several million points to represent a galaxy to save on computer processing time. A simulation of several million points could take many weeks to process. However, galaxies are made of billions to trillions of stars, so each point in the simulation actually represented large clusters of stars. The simulations were said to be of "low resolution" because many individual stars were smeared together to make one mass point in the simulation. The resolution of a computer simulation does affect the result, but it is not known how much of the result is influenced by the resolution of the simulation and how much the ignorance of the physics plays a role. Computer hardware speeds and the programming techniques have greatly improved, so astronomers are now getting to the point where they can run simulations with several billion mass points in a few weeks time. The computer simulations are also now incorporating more physical effects than just gravity and simplified hydrodynamics (gas motion) such as star formation, supernovae, formation of very large black holes at the centers of galaxies, electromagnetic fields, and other processes associated with ordinary matter. While dark matter makes up most of the matter in the universe and acts by the force of gravity alone, it turns out that smaller-scale effects from ordinary matter can make a significant impact on the structure and evolution of galaxies and clusters, much like differences in seasonings and leavening can greatly change the taste and texture of a baked clump of flour.

When two galaxies collide the stars will pass right on by each other without colliding. The distances between stars is so large compared to the sizes of the stars that star-star collisions are very rare when the galaxies collide. The orbits of the stars can be radically changed, though. Gravity is a long-range force and is the primary agent of the radical changes in a galaxy's structure when another galaxy comes close to it. Computer simulations show that a small galaxy passing close to a disk galaxy can trigger the formation of spiral arms in the disk galaxy. Alas! The simulations show that spiral arms formed this way do not last long. Part of the reason may be in the low resolution of the simulations.

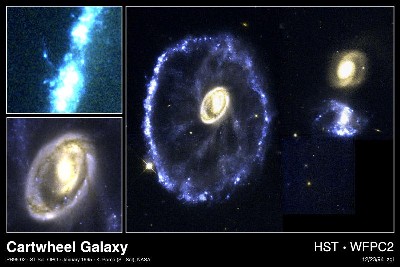

The stars may be flung out from the colliding galaxies to form long arcs. Several examples of very distorted galaxies are seen with long antenna-like arcs. In some collisions a small galaxy will collide head-on with a large galaxy and punch a hole in the large galaxy. The stars are not destroyed. The star orbits in the large galaxy are shifted to produce a ring around a compact core.

Select the "Antennae Galaxies formation movie" link below to show a movie of a computer simulation from Joshua Barnes showing the formation of the Antennae Galaxies. It is a Quicktime movie, so you will need a Quicktime viewer. The red particles are the dark matter particles and the white and green are stars and gas, respectively. Other collision movies are available on Barnes' Galaxy Transformations web site and on Chris Mihos' Galaxy Collisions and Mergers website.

Here are some photographs of examples of these collisions. The first is the Antennae Galaxies (NGC 4038 & NGC 4039) as viewed from the ground (left) and from the Hubble Space Telescope (right). Note the large number of H II regions produced from the collision. The second is the Cartwheel Galaxy as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope. A large spiral was hit face-on by one of the two galaxies to the right of the ring. The insets on the left show details of the clumpy ring structure and the core of the Cartwheel. Selecting the images will bring up an enlarged version in another window. See Mihos' galaxy modelling website for simulations of the creation of the Cartwheel Galaxy.

The gas clouds in galaxies are much larger than the stars, so they will very likely hit the clouds in another galaxy when the galaxies collide. When the clouds hit each other, they compress and collapse to form a lot of stars in a short time. Galaxies undergoing such a burst of star formation are called starburst galaxies and they can be the among the most luminous of galaxies.

Though typical galaxy collisions take place over what to us seems a long timescale, they are short compared to the lifetimes of galaxies. Some collisions are gentler and longer-lasting. In such collisions the galaxies can merge. Computer simulations show us that the big elliptical galaxies can form from the collisions of galaxies, including spiral galaxies. Elliptical galaxies formed in this way have faint shells of stars or dense clumps of stars that are probably debris left from the merging process. Mergers of galaxies to form ellipticals is probably why ellipticals are common in the central parts of rich clusters. The spirals in the outer regions of the clusters have not undergone any major interactions yet and so retain their original shape. Large spirals can merge with small galaxies and retain a spiral structure.

Some satellite galaxies of the Milky Way are in the process of merging with our galaxy. The dwarf elliptical galaxy SagDEG in the direction of the Milky Way's center is stretched and distorted from the tidal effects of the Milky Way's strong gravity. The Canis Major Dwarf galaxy about 25,000 light years from us is in a more advanced stage of "digestion" by the Milky Way---just the nucleus of a former galaxy is all that is left. A narrow band of neutral hydrogen from other satellite galaxies, the Magellanic Clouds, appears to be trailing behind those galaxies as they orbit the Milky Way. The band of hydrogen gas, called the "Magellanic Stream", extends almost 90 degrees across the sky away from the Magellanic Clouds and may be the result of an encounter they experienced with the Milky Way about 200 million years ago. At least eight other streams in the Milky Way from other dwarf galaxies have been found. The Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way will collide with each other 4.5 billion years from now and over the following two billion years after that initial encounter, they will merge to form an elliptical galaxy. The smaller spiral galaxy of the Local Group, the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) will also probably merge with us after that. (See the 2012 Hubblesite.org story which pegged the collision at 3.9 billion years from now for images and videos of the future collision.)

The giant ellipticals (called "cD galaxies") found close to the centers of galaxies were formed from the collision and merging of galaxies. When the giant elliptical gets large enough, it can gobble up nearby galaxies whole. This is called galactic cannibalism. The cD galaxies will have several bright concentrations in them instead of just one at the center. The other bright points are the cores of other galaxies that have been gobbled up.

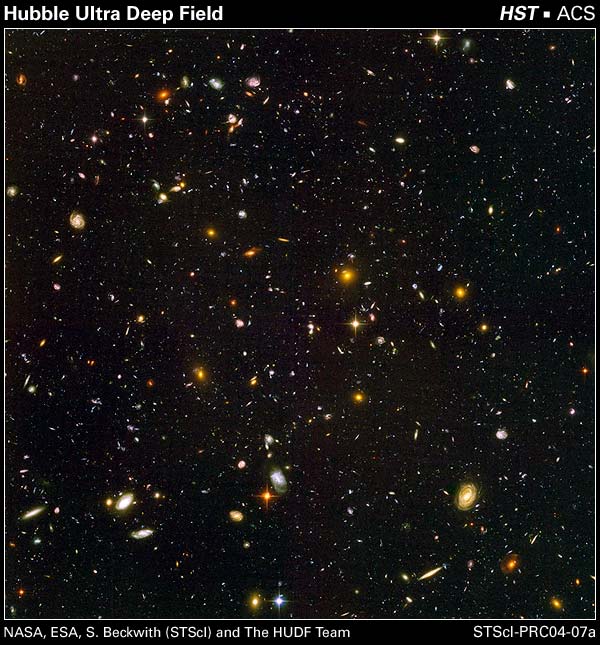

If collisions and mergers do happen, then more interactions should be seen when looking at regions of space at very great distances. When you look out to great distances, you see the universe as it was long ago because the light from those places takes such a long time to reach us over the billions of light years of intervening space. Edwin Hubble's discovery of the expansion of the universe means that the galaxies were once much closer together, so collisions should have been more common. Pictures from the Hubble Space Telescope of very distant galaxies show more distorted shapes, bent spiral arms, and irregular fragments than in nearby galaxies (seen in a more recent stage of their evolution).

The first image released from the James Webb Space Telescope was a deep field view of a different part of the sky in the Volans constellation---the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723. While Hubble's deep fields took weeks to generate, Webb was to create this view in just 12.5 hours---having a mirror nearly three times the diameter and instruments a couple of decades more advanced certainly makes a difference! (See the WebbCompare website for a slick interface overlap of the Hubble's view of SMAC 0723 [alternate link to Hubble view] with the Webb image.) This image is taken with Webb's near-infrared camera, so the infrared colors have been translated to visble band colors for us to see them. Note the warping of some galaxy images by gravitational lensing. In some cases the gravitational lensing will magnify the light of very distant galaxies that would otherwise be impossible to see.

In early 2010, astronomers announced that they were able to detect galaxies from the time of just 600 million to 800 million years after the birth of the universe (the Big Bang) using the new camera on the Hubble Space Telescope. A later study in 2012 found a cluster of galaxies beginning to form 600 million years after the Big Bang. Another study in 2012 called the Extreme Deep Field honed in on the center of the HUDF and detected galaxies forming just 450 million years after the Big Bang. A very deep look with the Spitzer Space Telescope in 2019 at two other patches of sky near the HUDF patch was able to get spectra of the H II regions (emission nebulae) in 135 galaxies at a stage less than a billion years after the Big Bang. Although these nebulae glow in the visible band, the light has been greatly redshifted into the infrared by the expansion of the universe to be detectable by Spitzer. It found that the early galaxies produced much more ionizing radiation that do modern galaxies. A detailed analysis of these early galaxies to figure out why they are so different than modern galaxies will have to wait until the much larger James Webb Space Telescope is trained on them.

The formation of galaxies is one major field of current research in astronomy. Astronomers are close to solving the engineering problem of computer hardware speeds and simulation techniques so that they can focus on the physical principles of galaxy formation. One major roadblock in their progress is the lack of understanding of the role that dark matter plays in the formation and interaction of galaxies. Since the dark matter's composition is unknown and how far out it extends in the galaxies and galaxy clusters is only beginning to be mapped (and see also link), it is not known how to best incorporate it into the computer simulations. Faced with such ignorance of the nature of dark matter, astronomers try inputting different models of the dark matter into the simulations and see if the results match the observations. As mentioned in the previous section, models that use "cold dark matter" of "WIMPs" provide the best fit to the observed structures. The recent discovery of "dark energy" is another major unknown in galaxy evolution models, though its effect may be more important to the future of the universe than to the origin and early history of the galaxies in which gravity and gas dynamics played the more significant role. On the observational side, the earliest stages of galaxy formation can be studied spectroscopically only in the infrared due to the expansion of the universe, so large infrared space telescopes like Webb or the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (launch date in 2025) are required to test the computer models.

There will be many new fundamental discoveries made in the coming years, so this section of the web site will surely undergo major revisions of the content. Although the content of our knowledge will be changed and expanded, the process of figuring out how things work will be the same. Theories and models will be created from the past observations and the fundamental physical laws and principles. Predictions will be made and then tested against new observations. Nature will veto our ideas or say that we are on the right track. Theories will be dropped, modified, or broadened. Having to reject a favorite theory can be frustrating but the excitement of meeting the challenge of the mystery and occasionally making a breakthrough in our understanding motivates astronomers and other scientists to keep exploring.

![]() Go back to previous section --

Go back to previous section --

![]() Go to next section

Go to next section

last updated: August 4, 2022