Video lecture for this chapter

There are other celestial objects that drift eastward with respect to the stars. They are the planets (Greek for ``wanderers''). There is much to be learned from observing the planetary motions with just the naked eye (i.e., no telescope). There are 5 planets visible without a telescope, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn (6 if you include Uranus for those with sharp eyes!). All of them plus Neptune move within 7 degrees of the ecliptic. This tells you something about of the orientation of the planet orbit planes with respect to the ecliptic---the figure below shows how flat the solar system is when viewed along the ecliptic plane. The planet positions, of course, do change as they orbit the Sun, but the orbit orientations remain the same. Many of the asteroids and dwarf planets also have orbits aligned fairly well with the ecliptic (within about 30 degrees).

The arrow pointing to Polaris in the solar system picture is tilted by 23.5 degrees because the Earth's rotation axis is tilted by 23.5 degrees with respect to the ecliptic. As viewed from the Earth, two of the planets (Mercury and Venus) are never far from the Sun. Venus can get about 48 degrees from the Sun, while Mercury can only manage a 27.5 degrees separation from the Sun. This tells you something about the size of their orbits in relation to the Earth's orbit size—their orbits are smaller and inside the Earth's orbit. When Venus and/or Mercury are east of the Sun, they will set after sunset so they are called an ``evening star'' even though they are not stars at all. When either of them is west of the Sun they will rise before sunrise and they are called a ``morning star''.

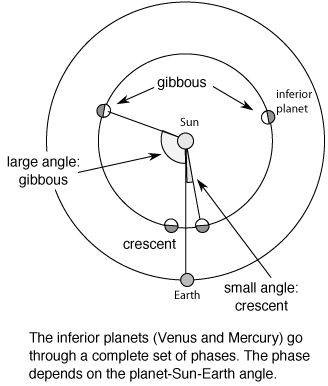

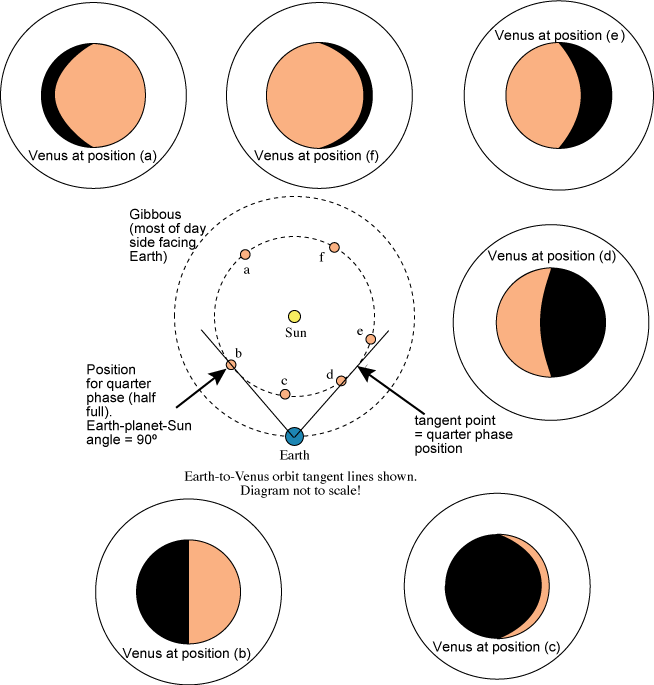

Planets produce no visible light of their own; you see them by reflected sunlight. True stars produce their own visible light. The planets inside the Earth's orbit are called the "inferior" planets because their distance from the Sun is less than (or inferior to) the Earth's distance from the Sun. Their closeness to the Sun enables us to see them go through a complete set of phases. The figure above shows how the phase of the inferior planets depends on the planet-Sun-Earth angle. The figure below gives more details of the inferior planet phases. When the planet is at the "tangent point" (where a line drawn from Earth to the planet's orbit intersects the orbit at only one point), it is at maximum separation from the Sun as seen from Earth and it appears to be in quarter phase. When the planet is farther from Earth than the tangent point, we see it in a gibbous phase and when it is closer to us than the tangent point, we see the planet in a crescent phase.

Because they can get between us and the Sun, Venus and Mercury can be seen in a crescent or new phase. This also explains why the planets outside the Earth's orbit, called the "superior planets", are never seen in a crescent or new phase. When Venus is in crescent phase, it is the brightest object in the sky besides the Moon and the Sun. Even though you see a small fraction of its sunlit side, it is so close to us that you see it appear quite bright. At these times, Venus is bright enough to create a shadow! The fact that you can see Venus and Mercury also in gibbous and nearly full phase proved to be a critical observation in deciding between a Earth-centered model and a Sun-centered model for the solar system.

Very rarely Venus is seen to go in front of the Sun. Such an event is called a "transit". Venus last transited the Sun in June 2012. The next transit won't happen for another 105 years! The Venus Transit page describes the 2012 Transit, the historical significance of transits for setting the scale of the solar system (to find the Astronomical Unit), and also how to view the Sun safely.

Because Mercury and Venus are closer to the Sun than we are (i.e., their orbits are inside the Earth's orbit), they are never visible at around midnight (or opposite the Sun). The superior planets can be visible at midnight. At midnight you are pointed directly away from the Sun so you see solar system objects above the horizon that are further out from the Sun than we are. [Careful readers will note that this is true for latitudes sufficiently far from the poles---if you are close enough to the poles, then the Sun can be visible at midnight and, therefore, Mercury and Venus as well.] If you want to see where the planets are in their orbits today or any other date, then go to the Solar System Live site (will display in another window). The orrery diagrams below illustrate the midnight view, the view for "evening star" positions, and the view for the "morning star" positions. The evening star view shows why the "evening star" planet can be seen only in the western sky after sunset and the morning star view shows why the "morning star" planet can be seen only in the eastern sky before sunrise. Select the images to enlarge them.

The animation below shows the rising, motion across the sky, and setting of an inner planet and an outer planet and how the observer's horizon position determines where the planets appear in the sky as the Earth rotates the observer around. The animation assumes the observer is far enough north in the northern hemisphere, so the solar system objects appear in the southern sky. In that case, objects to the right of the Sun are "ahead of" the Sun timewise (rising and setting before the Sun) and objects to the left of the Sun are "behind" the Sun timewise (rising and setting after the Sun). Note that the position of the Sun in the sky (with respect to the horizon) determines the time of day.

Ordinarily the planets ``wander'' eastward among the stars (though staying close to the ecliptic). But sometimes a strange thing happens---a planet will slow down its eastward drift among the stars, halt, and then back up and head westward for a few weeks or months, then halt and move eastward again. The planet executes a loop against the stars! When a planet is moving backward it is said to be executing retrograde motion. Perhaps it seemed to the ancients that the planets wanted to take another look at the stars they had just passed by.

The figure below shows Mars' retrograde loop happening at the beginning of 1997. Mars' position is plotted every 7 days from October 22, 1996 (the position on November 12, 1996 is noted) and the positions at the beginning and end of the retrograde loop (February 4 and April 29, 1997) are noted. An animation of this is available here. What causes retrograde motion? The answer to that question involved a long process of cultural evolution, political strife, and paradigm shifts. You will investigate the question when you look at geocentric (Earth-centered) models of the universe and heliocentric (Sun-centered) models of the universe in the next chapter.

last updated: January 18, 2022